The Moby Dick Theory of Big Companies

Examining Marc Andreessen's classic essay on when startups need to interact with a larger firm

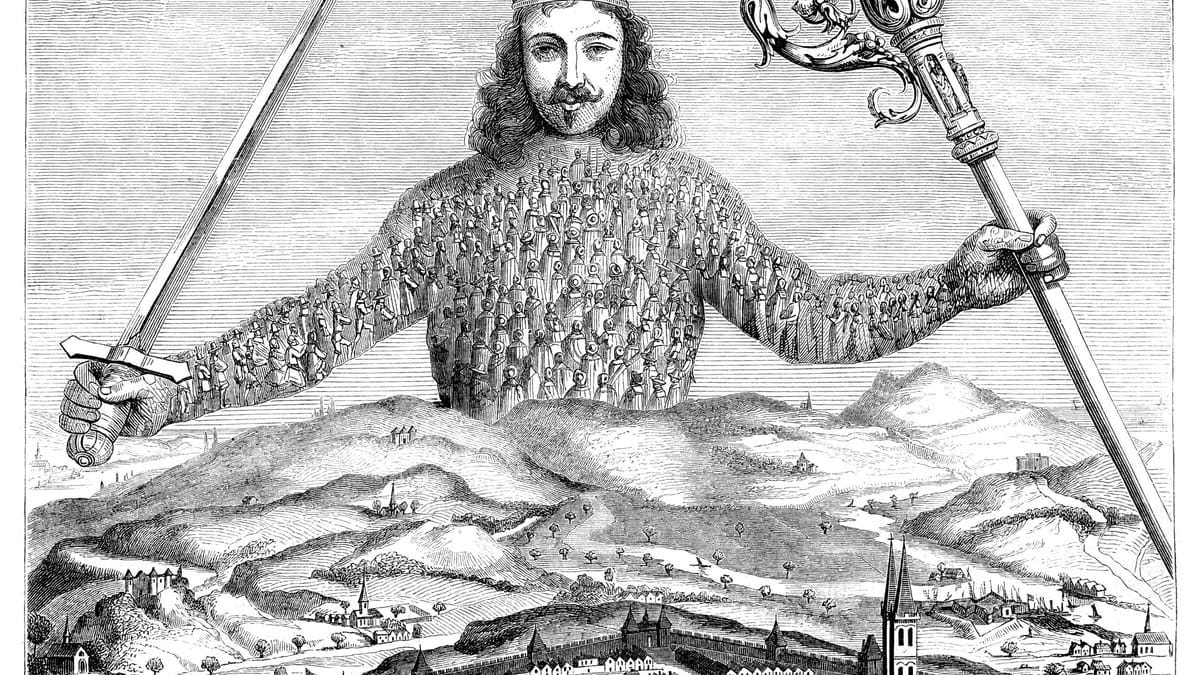

In Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, the state is depicted as an immense creature composed of countless individuals, each contributing to its powerful yet often inscrutable nature. Enterprises feel strikingly similar—enormous, complex beasts made up of thousands of individuals, divisions, processes, and competing interests. In my experience as a founder and startup executive, selling to these enterprise giants feels like Captain Ahab's pursuit of Moby Dick—full of uncertainty, obsession, risk, and occasionally tremendous rewards.

I’ve argued in a prior blog post, Why Startups Should Start with SMBs: Faster Sales, Stronger Foundations, that B2B startups are far better served by starting with SMB customers who can make decisions about your product quickly and start giving you product feedback immediately versus the long sales process that can be enterprise sales, but there are many examples of companies that pursue the enterprise path (for those of you looking to add even more difficulty on an already difficult journey).

Marc Andreessen captured this brilliantly in his essay, "The Moby Dick Theory of Big Companies," emphasizing how big companies' behaviors are fundamentally inexplicable from the outside. Inside these corporations, decisions are shaped by a chaotic mix of politics, ambitions, rivalries, budgets, and a thousand other hidden factors. Attempting to decode these internal machinations from outside the whale is a fool’s errand.

Navigating Enterprise Complexity

In past ventures like RPX and ZestyAI, our strategy was primarily enterprise-first. At Paxton, we wisely started by selling to SMBs before transitioning to enterprise deals—a journey that reinforced Andreessen’s warnings. At ZestyAI, it took nearly a year from pivoting into insurance to landing our first enterprise customer. Every deal demanded navigating through layers of bureaucracy: business units, purchasing departments, IT security, and occasionally the executive suite itself. Each stakeholder had veto power, and every "yes" required a careful orchestration of internal champions and allies.

Typically, enterprise sales follow a predictable yet arduous path. It starts by finding an internal champion—often a personal connection or a sympathetic ear from a trade show—who can help guide you through the complex maze. You'll likely pitch a pilot first to demonstrate your product's value. But even pilots require formal approvals, usually from purchasing and IT departments, which can add months to the sales cycle. Companies frequently demand competitive bids, unless your internal champion holds significant sway, and you'll often face pressure to offer free pilots. However, my experience suggests that insisting on even a modestly paid pilot helps validate genuine pain points and ensures you're investing resources wisely.

From Pilot to Production

Navigating the pilot successfully moves you toward a production contract, but the hurdles remain high. Enterprises prioritize process and stability, often resisting disruption—even beneficial disruption. Adoption means confronting ingrained habits, entrenched processes, and internal politics. You must align not only with your initial champion but with multiple layers of stakeholders, each holding influence over your product's success.

Ok, so you’ve gotten through the pilot. If you’ve defined success criteria for the pilot well, delivered on that and gotten the buy in from the appropriate people, now you can start negotiating a production contract. If you’ve done a paid pilot and went through purchasing and IT, then you should already be a vendor in their system so at this stage it’s more about negotiating with the department that will be using your product and integrating with their systems and processes. Another thing that is typically involved in enterprise deals are negotiations around services and support.

You may need to do some custom projects to help sweeten a deal with the company and provide ongoing support to the department that is purchasing your product. There is also change management - enterprises are very process driven so people get used to a way of doing things and you as a new vendor are disrupting that. Even if what you’re offering is a better way of doing something be prepared for resistance to change in the organization, but you need to make sure that what you’re selling is adopted into the companies processes because you’ll need to eventually negotiate a renewal.

Even after securing that initial deal, the work isn't done. Renewals introduce fresh challenges, especially if your initial sponsor leaves or is reassigned, leaving you vulnerable to new leadership eager to establish their own agenda. Clearly demonstrating ROI becomes crucial at this stage, usually involving agreed-upon metrics or a carefully maintained spreadsheet outlining the tangible benefits your solution delivers.

Purchasers vs. Users: Bridging the Gap

A critical dynamic in enterprise sales is the divide between purchasers and end-users. Purchasers control budgets and make buying decisions, while users experience the day-to-day benefits or drawbacks of your solution. Ideally, both should align—but often they don’t. Purchasers might prioritize cost savings or streamlined processes, whereas users emphasize practical functionality, usability, and quality of life improvements.

In early-stage startups, this divide can be particularly challenging. Often, feedback comes disproportionately from the purchaser side, skewing product development toward their priorities. It's essential to actively seek out user input to ensure your product genuinely addresses their pain points. The most successful enterprise startups balance these competing demands effectively, creating products valued both by decision-makers and end-users.

Ideally you can validate the need across many different companies (and hopefully they’re saying the same thing). When you are dealing with companies of a significant size (say $1B+ in revenues) they will often have idiosyncratic things that they (or the department head) are interested in and may have pain points that are unique to that person or organization. That’s why it’s important to try to find the commonalities between your potential customer and others in the same segment that you’re targeting. If they’re saying they need the same thing then that’s a good sign.

Integrations and Security: Gaining Trust

Integrations and security represent additional significant hurdles. Enterprises, rightly risk-averse, demand robust security assurances. Achieving certifications like SOC2 Type 1 (with assistance from platforms like Vanta, Sprinto, or Drata) and navigating exhaustive security questionnaires become prerequisites for even initial discussions. These questionnaires, often hundreds of items long, test your ability to meet stringent enterprise standards.

They are there to say no - if they integrate with you and you cause a problem, they will get blamed for not catching the issue. If you do well and deliver value, they will probably never hear from you again and no one’s going to thank them or congratulate them, there is an asymmetric downside risk of the company for them personally. So definitely remember to take care of them, they’re usually the ones saying no to exciting new things and getting people to pump the breaks. They can’t make a deal happen though (unless you’re pitching them a cybersecurity solution), but they can say no to you.

IT and security teams have asymmetric incentives—they rarely receive recognition when integrations go smoothly but inevitably face repercussions when things go wrong. Understanding and addressing this dynamic is key. Demonstrating reliability, transparency, and proactive security measures can earn trust and make IT teams more willing to advocate internally for your solution.

Legal and Contracting: Mitigating Enterprise Risks

Legal and contracting departments represent formidable obstacles. Similar to IT, their primary role is risk mitigation. Legal teams rarely gain recognition for smooth deal executions but face scrutiny when problems arise. Effective enterprise sales require navigating lengthy negotiations, complex contracts, and stringent legal reviews.

Having a strong internal champion who understands and can advocate within these processes is invaluable. The best legal teams partner closely with business units, balancing speed with risk mitigation, though this is uncommon. Often, legal teams are understaffed and cautious, underscoring the need for patience, clear communication, and thorough preparation on your part.

Managing Timelines and Expectations

Managing timelines and priorities is critical in enterprise sales. Startups often treat enterprise deals as existential milestones, while enterprises may view them as relatively minor. Enterprises operate on unpredictable timelines, often cycling rapidly between periods of urgency and extended inertia. As a startup, you're typically forced to adapt quickly and without leverage when enterprises suddenly shift their demands.

Balancing this dynamic requires strategic resource allocation, diversification of your sales pipeline, and careful expectation management. Overreliance on a single enterprise deal can be perilous; successful startups maintain flexibility, proactively managing resources and relationships to withstand inevitable delays and unexpected shifts.

For you as a startup, the deal with the big enterprise will feel like it means everything to you. For the enterprise, it could matter less. You have no leverage in this case. The company that you are selling to will be fine if they don’t do a deal with you. They’ll go quiet for a couple of months and then suddenly reappear and demand things immediately and you’ll just have to acquiesce to it because they could represent 30% or more of your startup’s revenues. So while you wait for that first deal to close you’ll be burning cash on product development (hopefully you’ve done enough market validation to ensure you’re building in the right direction) and a lot of your time will be spent building relationships within the enterprise, navigating its bureaucracy and doing the same thing at other big enterprises

Avoiding Ahab’s Fate

In sum, successfully navigating enterprise sales demands patience, strategic relationship-building, meticulous preparation, and adaptability. The potential rewards are enormous—but so too are the risks. Embracing Andreessen’s cautionary insights and grounding your approach in practical experience can help your startup avoid becoming another Captain Ahab—consumed by obsession, overwhelmed by complexity, and ultimately capsized by the unpredictable enterprise leviathan.